Why did I forget these names? Should I have written them down? I feel like story-telling would have helped me to remember. One of my close friends is a fantastic story-teller. This trait is not only enjoyable but helps him to remember. On a personal level, story-telling aids memory and builds relationships through sharing experiences. How do I share South Africa with people back here in Colorado? I intend to work on my story-telling abilities. These personal experiences with story-telling reaffirms the importance of story-telling for a nation. Furthermore, I still believe in the importance, beauty and potency of oral tradition. It is a direct human-to-human interaction versus recording on paper, film or photographs.

Why did I forget these names? Should I have written them down? I feel like story-telling would have helped me to remember. One of my close friends is a fantastic story-teller. This trait is not only enjoyable but helps him to remember. On a personal level, story-telling aids memory and builds relationships through sharing experiences. How do I share South Africa with people back here in Colorado? I intend to work on my story-telling abilities. These personal experiences with story-telling reaffirms the importance of story-telling for a nation. Furthermore, I still believe in the importance, beauty and potency of oral tradition. It is a direct human-to-human interaction versus recording on paper, film or photographs.At first, I was a little bothered by all the museums that we visited in South Africa. I wanted to see the people. However, my new views on story-telling have shown me a crucial purpose for museums. We talked about memorialization and truth-telling while in South Africa. As an anthropology major, I focus on culture and didn’t at first see museums as part of culture. My current appreciation of museums is a result from understanding their impact on culture. Maybe, “understanding” is the wrong word. I am almost in awe of their potency. Who’s history is being told and how it is told seem obvious components to notice, but museums can have a subtle or covert effect on the mind.

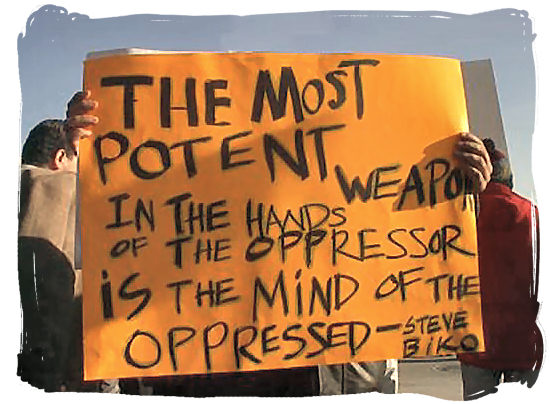

To side track, I finally watched Cry, Freedom. Like museums, the oppressive apartheid culture had an effect on the minds of black South Africans that Steve Biko pointed out and addressed with black consciousness. Black South Africans were made to feel dirty, less worthy, or ugly. It is not that people are stupid for being affected by an oppressive culture or even museums.

Again, I am awe of how these effects occur. Cry, Freedom was another personal means of story-telling and remembering the experience. I watched the film with my mother and she had a lot of questions. The film was a great means of trying to explain what I had done and seen in South Africa.

Again, I am awe of how these effects occur. Cry, Freedom was another personal means of story-telling and remembering the experience. I watched the film with my mother and she had a lot of questions. The film was a great means of trying to explain what I had done and seen in South Africa.Back to the issue of museums. I have been thinking a lot about the Native Americans and their forgotten history in our country. I was recently in Durango where the Anasazi Heritage Center is located. I did not get a chance to visit the center but hope to visit it in the near future. What I have learned about the center indicates the importance of language. Descendants of the “Anasazi” do not necessarily like the word “Anasazi” but cannot agree on an alternative like Navajo or Pueblo peoples. When a word identifies you, it becomes of utmost important to be correct. The power of words amazes me (again like museums). How can you tell a forgotten history when a single word cannot be agreed upon? Is the conflict over the single word a result from the history being forgotten and the peoples being oppressed?